Most people can sense when a conflict is brewing in their personal relationships. But what if their smartphones could, too — and could intervene during the moments before an argument boiled over? That’s the idea behind a developing technology that could detect and mediate relationship problems by tapping into data from smart devices.

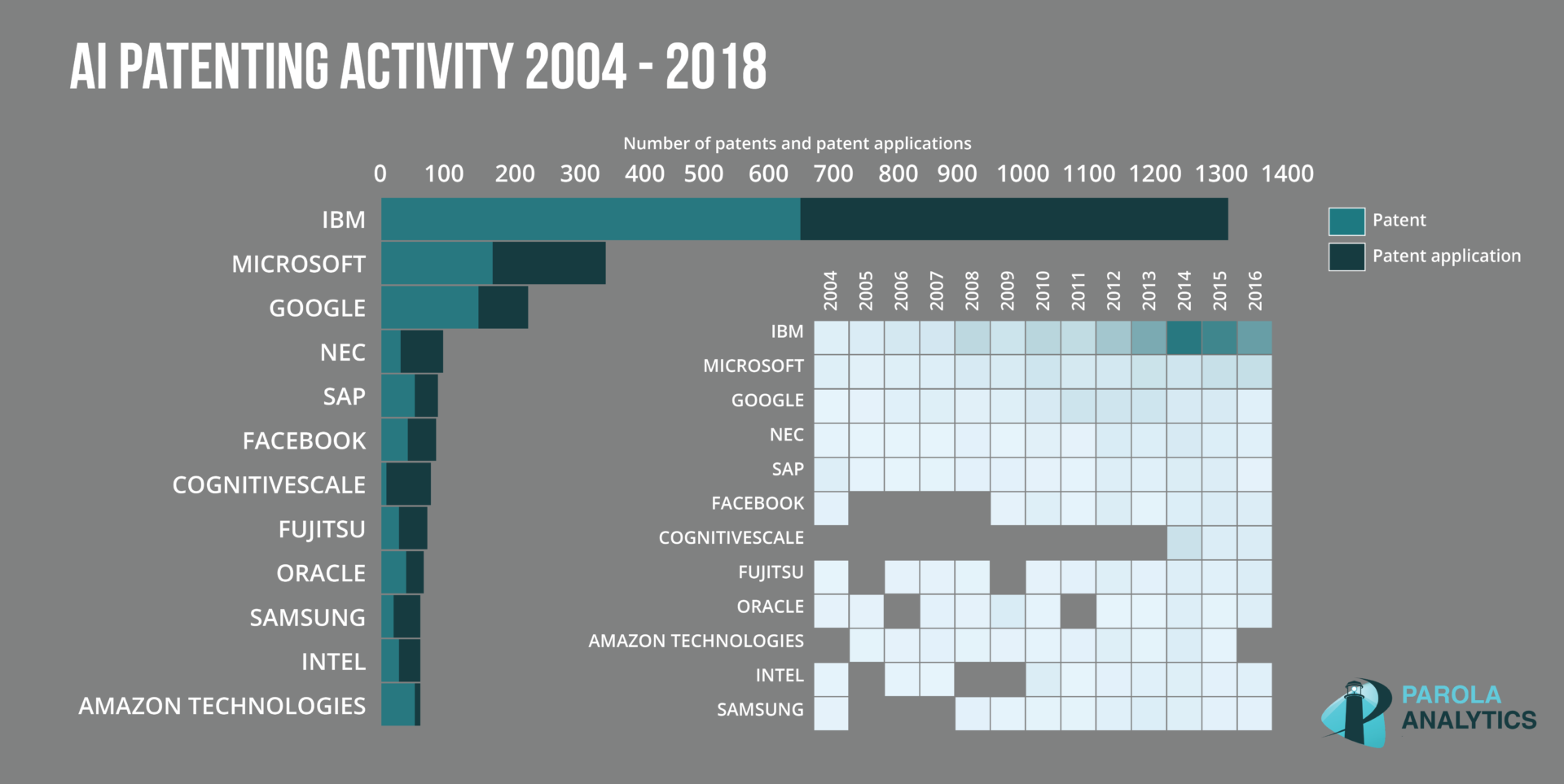

A machine learning-based method that uses data from smartphones and wearable sensors to predict interpersonal conflicts has been presented in a patent application filed with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. The long-term vision is creating a downloadable app that would support emotional well-being and healthy relationships, Adela Timmons, an assistant professor of psychology at Florida International University and the principal investigator on the project, told The Academic Times.

“The idea is that if you could send an intervention to someone in the moment of need, or even right before the moment of need, and in the natural context in which it’s occurring, your intervention is going to be more effective than, say, having someone coming into a therapist’s office for one hour a week,” Timmons said. “There’s a hope among some psychologists that we might be able to increase the effectiveness of interventions if we can meet people where they’re at both in time and in place.”

In a previous study, Timmons and her colleagues conducted a field experiment in which couples wore sensors that tracked body temperature, heart rate and perspiration, concluding that it’s possible to use sensor data from smartphones and wearable devices to predict emotional states in real-life environments.

“Your phone or wearable device can collect a lot of different pieces of information about you — for example, your heart rate or who you’re physically with through GPS tracking,” Timmons said. “They can also take measurements of your vocal pitch or tone or analyze speech for the frequency of emotional words.”

The researchers found that seemingly unrelated data streams provided by smart devices proved to be surprisingly relevant to interpersonal relationships, she said. For example, the researchers could determine when somebody was driving a vehicle, based on how fast they were moving, and found that higher rates of speed were modestly predictive of when couples were having a conflict.

But no individual factor alone was highly associated with interpersonal conflict: A person’s heart rate could rise due to exercise or exposure to heat rather than an upsetting exchange with their partner, Timmons said. By drawing from multiple streams of data, however, the researchers created algorithms capable of accurately detecting interpersonal conflict.

In theory, the technology could track indicators of interpersonal functioning and provide suggestions for how to resolve conflicts. For example, the app might detect a rising heart rate and changes in vocal tone and suggest the user take a walk or perform breathing exercises before reengaging with their partner.

Ideally, the intervention would occur in real time, when an argument starts to escalate but before it gets out of control, Timmons said. In the aftermath of an argument, the technology could possibly assist in reconciliation as well.

The researchers are hopeful that their invention will help decrease barriers to mental health care. Though smart devices and internet connections remain expensive and unavailable to many people, internet access is steadily expanding.

“It’s far less expensive to provide someone with a smartphone or internet connectivity than the standard model of traditional therapy,” Timmons said.

On the darker side, the concept could be alarming for people who don’t want their smartphone listening to their intimate conversations, or who believe that algorithms should stay out of human relationships. Acknowledging that new technologies can be wielded irresponsibly, Timmons said that, in this case, the development process has been driven by psychologists and other experts in an effort to create science-based interventions that can be scaled to be widely accessible to the public.

She believes it’s important to be “very clear” with users about what information is collected and how it’s used, and she called for regulation of the ethical use of data to protect users.

“There are a lot of ways technology can help us and a lot of ways technology can hurt us,” Timmons added. “I tend to view technology as not being good or bad in and of itself; it’s the way that humans use it, design it and interact with it that determines its impact. I think it comes down to ethical and responsible development and use.”

At this point, the technology is still in the conceptual stage. The research team has developed proof-of-concept algorithms to support the development of an app. They have also secured funding to test the system’s accuracy and conduct a randomized controlled trial. Timmons estimates that the project is still about four years away from potentially delivering real-time reminders aimed at helping people solve communication issues with their loved ones.

The application for the patent, “Expert-driven, technology-facilitated intervention system for improving interpersonal relationships,” was filed March 2, 2018, with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. It was published May 13, 2021, with the application number 2021/0142884. The inventors on the pending patent are Gayla Margolin, Adela C. Timmons, Matthew William Ahle, Theodora Chaspari and Shrikanth Sambasivan Narayanan. The applicant is the University of Southern California.

The article “Smart devices could someday help save your relationship”, written by Howard Hardee was first published in the Academic Times. Parola Analytics provided the technical research for this story.