Difficult to remove and highly carcinogenic, arsenic is one of the most common water contaminants around the world, with millions of people drinking it every day. But that number may start to drop as newer, cheaper purification technology emerges — and U.S. researchers have invented one method that could make an impact in developing countries, especially.

To help solve global arsenic exposure, University of California, Berkeley researchers applied for a patent for a water purification device that they say will cheaply and efficiently remove arsenic from water, specifically targeting its use for impoverished areas around the world, the U.S. and other industrialized countries. They say the technology differs from other approaches in that it is safe and easy to install, as well as faster than previous designs.

The World Intellectual Property Organization published the application, which resulted from a project dating back to 2005, on Feb. 25.

“We started working on an affordable, effective way to remove arsenic from drinking water, which affects 200 million people around the world, most of them rural and in developing countries,” said Ashok Gadgil, an environmental engineering professor at UC Berkeley. “There is no reliable, robust way to remove arsenic for poor communities.”

Arsenic is commonly found in groundwater that is used for drinking, food production and agriculture, and long-term consumption may result in various cancers, skin problems and diabetes. Arsenic has been a major public health problem in impoverished countries such as Bangladesh for years, where contaminated well water is ubiquitous.

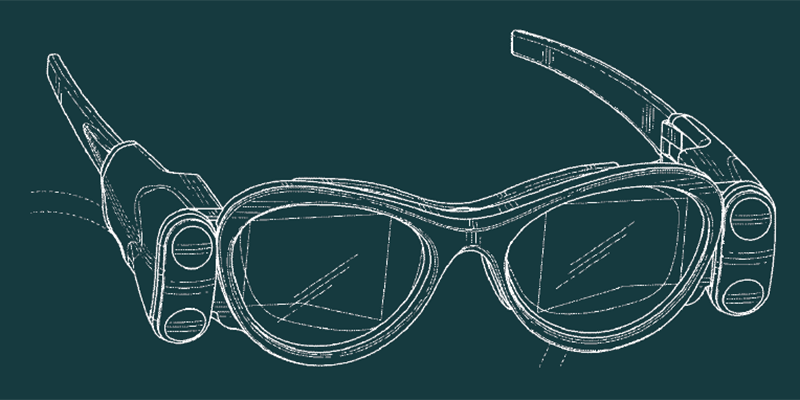

Gadgil and his team developed a “high performance” iron electrocoagulation reactor that is relatively low-tech. It features a coil of iron lined with electrodes. A weak electric voltage releases a small amount of metal from the coil into the water flowing through it. This sets off a chemical reaction that bonds arsenic to dissolved particles of iron or steel, creating a tight molecular bond that allows the iron to grab up the arsenic, which can then be filtered out. Manipulating this process can remove other contaminants as well, such as chromium, and adding a powerful oxidizer such as hydrogen peroxide speeds up the chemical reaction by a factor of 10,000, according to Gadgil.

This entire process takes place within a simple cartridge that anyone could install.

“That makes it even easier for someone in a rural area with low-level science education, because it is like changing an oil filter,” Gadgil said in an interview with The Academic Times. “You don’t need to know what’s inside it or how it is built — you simply take it out, throw it away or return it for recycling and pop in a new one.”

Prior to applying for the patent, in 2016, Gadgil founded a small demonstration plant in West Bengal, India, near Bangladesh, which currently provides drinking water to a community of around 5,000 people. He used an older reactor that creates its own oxidizing agent, which is more suited to areas where hydrogen peroxide may be difficult to come by.

In the future, Gadgil and his team plan to build a new test site on a farm in Allensworth, California, a small agricultural community near Bakersfield, using an external pump to add hydrogen peroxide. At this stage, the water at the Allensworth site will only be used for farming and doesn’t depend on patent approval, but Gadgil ultimately wants to use this reactor to create safe drinking water for communities of 500 to 600 people, and scale it up further over time.

“The goal is to not just dump the responsibility of operating the plant on the individual, because when you do that, people who are marginalized economically cannot get safe drinking water,” said Gadgil. “And safe drinking water even the U.N. recognizes as a fundamental human right.”

In the U.S., the Environmental Protection Agency sets a maximum contaminant level, or MCL, for safe drinking water, allowing for small amounts of various contaminants including arsenic. Currently, the MCL for arsenic is 10 parts per billion, or 10 micrograms per liter. But it wasn’t always that way. Starting in the 1940s, arsenic’s MCL was 50 parts per billion, until President Bill Clinton lowered it to 10 parts per billion three days before he left office. The George W. Bush administration initially halted that regulation but quickly reconsidered, allowing the MCL of arsenic to fall back to 10 parts per billion by 2006.

But Gadgil says that’s still a potentially fatal amount. According to Gadgil, if 100,000 people drink water contaminated with arsenic at 10 parts per billion, 740 more people than is typical for the population will develop internal cancers as a result. That means 50 parts per billion would lead to 3,700 excess cancer cases among the same group of people.

But Gadgil aims to bring the worldwide presence of arsenic in water down to less than one part per billion.

“My hope is that arsenic poisoning will become a thing of the past,” said Gadgil.

The application for the patent, “High Performance Iron Electrocoagulation Systems for Removing Water Contaminants”, was filed on Aug. 12, 2020 to the World Intellectual Property Organization. It was published Feb. 25, 2021 with the application number PCT/US2020/046028. The earliest priority date was Aug. 22, 2019. The inventors of the pending patent are Ashok Jagganath Gadgil, Arkadeep Kumar, Mohit Nahata and Siva Rama Satyam Bandaru, University of California, Berkeley. The assignee is the Regents of the University of California.

The article “New water purifier could help remove arsenic from drinking water”, written by Kevin Wheeler was first published in the Academic Times. Parola Analytics provided the technical research for this story.